A Historical Overview of Harpur's Ferry

In October of 2012, founder Sal Caruana reached out to the agency and was generous enough to offer a first hand narrative of the founding of Harpur’s Ferry. In the 40 plus years since Sal Caruana, Jon-Marc Weston, and Adam Bernstein founded the agency, we have grown exponentially with the same values in mind: the wellbeing of the Binghamton University Community.

When Harpur’s Ferry began, it was with essentially no resources and a used Cadillac Hearse. Today, with the unwavering support of the University, alumni, and the community we respond with a fleet of modern vehicles with the best and latest in medical equipment. Below is the letter from Sal Caruana with insight into the origins of our squad.

The Founding of Harpur's Ferry at Binghamton University

Key parts of the Harpur’s Ferry story are the related events that led up to its creation and the campus climate in 1970-72. This period was the apex of both “hippie culture” and hallucinogenic drug use that began in the mid ‘60s. LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) usage in particular was a serious and wide-spread problem on our campus. “Acid” was a drug that was often dangerous and unpredictable, and the duration and intensity of its effect would vary widely from user to user. It was not uncommon to see “trippin’” students in manic or incoherent states sprawled on couches in the Student Center or residence hall lounges; rather, it was a fact of daily life at Binghamton University. The Administration’s policy towards the obvious was “don’t ask, don’t tell”. It sounds so incredible today, but back then benign neglect was the way it was managed on most college campuses when it came to hard drugs. Binghamton University had a first rate infirmary and brand new School of Nursing; however, as for campus drug counseling all we had was a student run program called High Hopes which was located in a small room behind the Post Office. It had 3 cots, some drug literature and one student volunteer on duty 24/7. It wasn’t a clinic; it was a place your friends brought you to when your acid trip turned bad or freaky and you were in serious need of constant observation until you “came down”. Sadly, the days of colleges providing students with professional and high level health, safety and counseling services were still some years away.

The most dangerous time for LSD abuse on our campus was during rock concerts and never more so than when the Grateful Dead roared into town. Owsley Stanley, the group’s sound engineer kept both the band and audience fueled on the drug. Years later he admitted to giving out “millions of hits of acid” to audience members over the group’s career, and he no doubt was largely responsible for creating the army of “Deadheads” who followed their tours around the country. The Dead’s concert in the new West Gym on Saturday May 2,1970 became a legendary concert in the history of both rock music and the band, and is considered by many music critics to have been their finest live performance ever. Bootleg copies of “The Harpur College Tapes” have been in circulation and prized for decades, and now can be found on-line in a 3 CD set for $100. Including their new opening act (New Riders of the Purple Sage) the show lasted almost 6 hours, on a fateful day that had marked the start of nationwide student unrest when it was revealed the Nixon Administration was bombing Cambodia in pursuit of its Viet Nam objectives-a war they said was ending. Two short days later, tragedy struck and campuses everywhere exploded in rage when a college protest against the Nixon Administration at Kent State University resulted in the shooting deaths of 4 students by members of the National Guard.

At this point it is important to also mention the serious tension that had already existed between the Binghamton community and our student body that had been building since 1966 and the days of the first student political marches to the downtown Court House. Five years later, in May 1970, the growth of the drug and hippie culture on campus was colliding daily with the conservative working class community and had created mutual distrust and dislike between students, local residents and their leaders. Unfortunately, our students also projected this distrust and animosity towards our Campus Security who became convenient proxies for “the establishment”, and their presence at large events was avoided whenever possible. In their place groups of student volunteers were often asked by event organizers to be ticket takers, ushers and crowd-controllers if needed, and on the night of the Dead concert many of the members of the TAU Alpha Upsilon fraternity were serving in these functions.

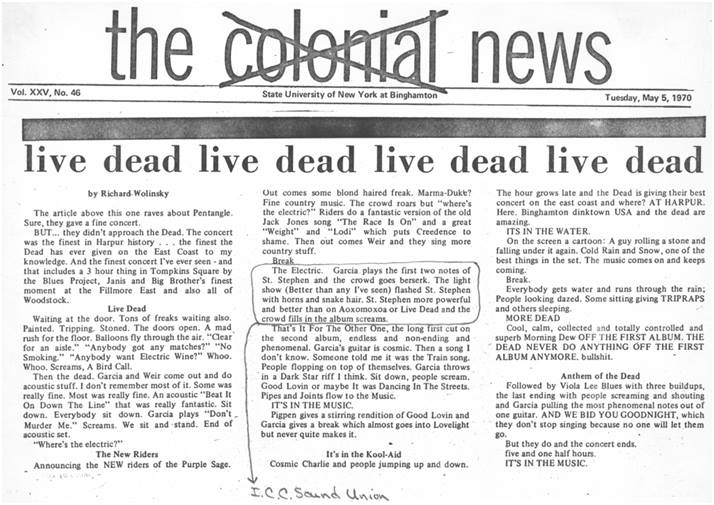

What was this historic concert really like? Enlarge the image above, and read the May 5, 1970 review that appeared in the school newspaper (formerly called the Colonial News, the Xed out title signified both an anti-colonial political statement and the search underway for a new name). The name soon chosen was “The Pipe Dream”-an opiatic reference that fit the times, and also the work-product of some of the reporters trippin’ on the job:

Unfortunately, there was another story that night; a tragic and chaotic scene witnessed by only a few which was never reported and remains a mystery still. The concert staffers were all asked to remain until everyone had left the building. When the West Gym finally emptied around 1:30 a.m. there were eight lifeless bodies left on the floor, in various drug-induced states, and no one on the scene qualified to assess or treat these individuals. Students rushed to make frantic calls from the gym office to campus security for help (although EMT training was not yet part of their skill set) and to local hospitals for ambulances. The conversations with hospital dispatchers were troubling, and the indifference our callers were sensing was thought by some to be “hippie payback”. (Today, decades later and in fairness to those dispatchers, our perceptions clearly might have blurred by the agitation and impatience that commonly besets those who call for emergency assistance.) Since we were not sure what responses Campus Security was receiving to their ambulance calls too, and with no ETA’s in hand, we made a quick and frenzied decision to load the students into our cars and race to the three area hospitals. Why three? There was discussion that we couldn’t risk overwhelming one hospital, or also risk more hippie payback (waiting-room limbo) if we chose the wrong hospital for all of our sick. So, we purposely scattered to Binghamton General, Lourdes and Wilson. Were we paranoid? Perhaps, but we thought of it as being careful. Once at the hospitals our victims were promptly accepted and treated, and we were advised to go home. As we left we realized we did not know any of their names, and that none had been recognized by us as Binghamton students.

News of the eight overdosers or their outcomes never appeared in the campus paper or Sun-Bulletin. In those days before federal law for Uniform Crime Reporting to the Department of Education, every campus kept those secrets as best they could. Though fatalities were never confirmed, those of us who kept asking questions heard one story or rumor repeatedly: three of the victims had died and none of them had any Binghamton connections (they were either Deadheads and/or students from other upstate colleges). To those of us who were there the possibility of fatalities was certainly credible. An information blackout from the hospitals and university would be credible too, as both would be worried about potential legal liability in managing or mismanaging the response. Over the years I have also wondered about this: if fatalities had occurred and that news was added to growing campus discontent ( college students nationwide were protesting, striking and rioting over Kent State deaths), how angrier yet would the campus/community dynamic have become as our college was moving quickly too into a protest phase? About that phase: less than one week after the Grateful Dead concert our students and Faculty Senate voted to strike; classes were suspended for the semester, finals were student-optional (some students needed to improve their grades to graduate or for grad school), the dorms remained open, and daily protest marches from the Vestal campus to downtown Binghamton began, led by University President G. Bruce Dearing who was jeered loudly and spat on by local citizens along the route.

When the campus community returned for classes in the Fall of 1970, much of what happened that past May was put aside. Students were once again self-absorbed in their studies, with many men striving to get into grad school largely to avoid the Viet Nam draft and Nixon’s escalating war- a loophole that was soon closed. As for the Grateful Dead concert, whenever it was talked about at our Sunday night TAU meetings in the Student Center, or at Thursday beer and pizza nights at our favorite downtown bar, Al’s on Court Street, the chaotic aftermath was always a part of those conversations as well as feelings of despair and frustration. The birth of Harpur’s Ferry had begun.

In the Fall of 1972 the student founder of High Hopes, Adam Bernstein ’73 was faced with a growing problem at his facility. In larger numbers drug -overdosed students were calling or arriving in distressed conditions that required emergency medical attention. Rather than hoping or begging for a local ambulance response, the fastest means of transportation to an area hospital at the time were Campus Security patrol cars which were limited in availability and not yet equipped with overhead lights or sirens. Adam approached his good friend TAU Brother Jon-Marc Weston for help, and together they asked the Administration to support the idea of a volunteer ambulance. The Administration was in fact very supportive in an all too familiar way: “Great idea!…sorry, no money…good luck”.

When Jon-Marc began looking for money he pitched the idea to his Brothers in the TAU fraternity and it struck a raw nerve for those of us who were involved in the Grateful Dead crisis. We emptied our treasury to support the project, raised money in the campus community, and made personal donations too. At the finish line Jon-Marc and Adam both contributed their bar mitzvah money to complete the funding. As the largest donor, TAU asked to participate in the naming. As TAU President that semester, and as a history major fresh from Professor Albert (“Colonel Al”) House’s course on The Civil War and Reconstruction( known then as History 273), I led our discussion by suggesting the name Harpur’s Ferry. Sure, it sounded catchy as a word-play, but there was more to it than that. Harper’s Ferry (West Virginia) was the site of John Brown’s attack in 1859, and the beginning of armed conflict that led up to our Civil War. Harper’s Ferry had truly marked a historic beginning, and my thinking was that our Harpur’s Ferry could be a historic beginning too, the beginning of a new era in getting students more quickly to the emergency care they may need to save their lives. Of course many of my TAU Brothers liked the word-play but could care less about the history; then again, those were also the guys who were majoring in the campus drinking game called Wales Tales (in the decades before Beer Pong). In fact, most of the frat was pro-beer and anti-drug (the eternal student conflict), so it came as little surprise that second place in the ambulance naming contest went to “High and Hopeless”. Frat humor at its best, but the High Hopes staff was not amused.

The first vehicle for Harpur’s Ferry actually predates the TAU funding. Earlier Jon-Marc had seen a 1950’s Cadillac hearse advertised for sale by a Johnson City funeral home. It had a zillion miles but was affordably priced at $125. He bought it with his own money which he hoped to recoup from future donors, and he soon found out why it was so cheap-it was nearly as dead as its many horizontal passengers, and the rig quickly ended up in the automobile graveyard.

For the second vehicle (first to be put into service) Jon-Marc did a little research this time. He found out that fire departments in New York had to replace ambulances every 10 years, and he soon set his sights on a hearse style unit that was coming up for sale for $1200. Today he explains that “to understand the automobile value of $1200 in 1972, a new BMW 1600 was then selling for $2500″. This was a lot of money by anyone’s standards, especially for college students who were habitually broke. Nevertheless, the Ferry was purchased with TAU’s help, and what amazingly happened next is a story best told by Jon-Marc himself:

“While we were arranging for training for our initial cadre the Administration was getting cold feet. Concerns over liability were raised, as if having someone die in the back of a campus squad car on the way to the hospital or waiting for an ambulance from town wasn’t a liability! Adam and I decided to push the issue and took the ambulance on a campus tour with sirens and lights flashing. We were chased down, chastised and the ambulance was impounded. Tragically while negotiations continued a student was shot on campus by a non-student, and he died of his wounds. While it was not clear that an on-site ambulance would have made the difference, in this case it was obvious that it was an idea whose time had come.”

Many of the first volunteers were pre-med and pre-dent students. The training? Group leaders were chosen and trained in First Aid at the Binghamton Red Cross downtown. They brought the training and curriculum back to campus and our first cohort, some of whom had learned CPR as summer lifeguards. So, if in route to the hospital you needed mouth to mouth or chest compressions you were in good hands. But if you needed anything more, you best start praying for a fast ride. The equipment? A stretcher, some blankets, towels and a First Aid kit. Initially the largest volunteer cohort was from TAU, and it included Paul Burns ’73, Al Plumser ‘ 73 and Steve Chartan ’73-who with Jon-Marc all became doctors. They, Adam Bernstein and I, and many others who worked to create Harpur’s Ferry graduated in its very first year when it was still a work in progress. Those of us who have remained connected to the University over the decades have seen its incredible growth and success, and the dedicated professional service of so many men and women. The levels of university and community support that have enabled such costly vehicles, training and equipment have been incredible too and a startling contrast to the early days. Please permit me to say on behalf of all of us who were there are the start that we are humbled, thankful and uplifted by all who came after. To borrow some from my Brother Jon-Marc: Harpur’s Ferry is an idea whose time should never end.

Sal Caruana ‘ 73